CLOUD

CLOUD

CLOUD

CLOUD

CLOUD

CLOUD

It looks like hybrid cloud is finally here.

We’ve seen a decade of posturing, marketecture, slideware and narrow examples, but there’s little question that the definition of cloud is expanding to include on-premises workloads in hybrid models. Depending on which numbers you choose to represent information technology spending, public cloud accounts for less than 5% of the total pie. As such there’s a huge opportunity in hybrid, outside of the pure public cloud; and everyone wants a piece of the action.

So the big question is: How will this now evolve? Customers want control, governance, security, flexibility and a feature-rich set of services to build their digital businesses. It’s unlikely they can buy all that. They’re going to have to build it with partners — specifically vendors, systems integrators, consultancies and their own developers.

The tug-of-war to win the new cloud day has finally started in earnest – between the hyperscalers and the largest enterprise tech companies in the world.

In this Breaking Analysis, we’ll walk you through how we see the battle for hybrid cloud — how we got here, where we are today and where it’s headed, with some fresh data on operating expense versus capital expense from Enterprise Technology Research.

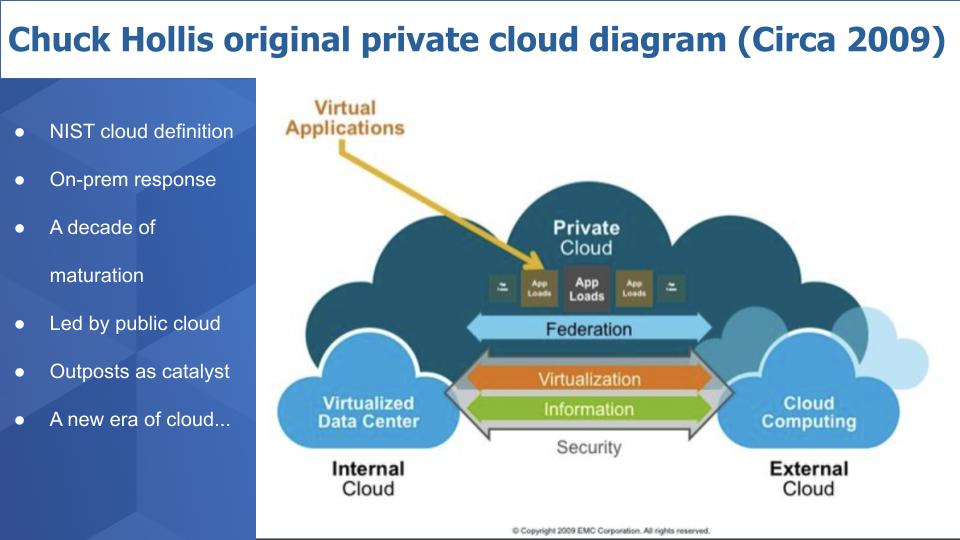

First let’s go back to 2009 and a blog post by a man named Chuck Hollis.

Chuck Hollis at the time was a chief technology officer and marketing guru at EMC Corp., which owned VMware Inc. Chuck was a hybrid, multitool player (pun intended). EMC had a lot at stake as the ascendency of Amazon Web Services Inc. was threatening the historical models that had defined enterprise IT infrastructure procurement, deployment and management.

It was around that time that the National Institute of Standards and Technology published its first draft of a cloud computing definition, which if memory serves correctly, included language to the effect of accessing remote services over the public network. NIST has since evolved the definition, but the original was very favorable to the public cloud providers – and the vendor community said, “Hang on — we’re in this game too.”

That’s when Chuck Hollis created the above diagram. He called it “Private Cloud,” a term that he first saw buried in a Gartner Inc. research note that hadn’t fleshed out the concept visually. Chuck was good at communicating through graphics and took at stab at the future of cloud.

The idea was pretty compelling. The definition of cloud centered on control, where you had on-premises workloads that could span public clouds and on-prem data centers with federated security, plus a shared data layer that spanned estates. Essentially you had an internal cloud and an external cloud with a single point of control.

The term private cloud morphed into the on-prem domain, but Hollis’ diagram is what the hybrid cloud vision has become: an abstraction layer that spans on-prem and public clouds. And we can extend that across clouds and out to the edge – where a customer has a single point of control with federated governance and security. Now we know this is still aspirational. It doesn’t exist in a complete form today. But we’re now seeing vendor offerings that put forth this promise and a roadmap to get there from different points of strength that we’ll talk about.

The NIST definition now reads:

Cloud computing is a model for enabling ubiquitous, convenient, on-demand network access to a shared pool of configurable computing resources (e.g., networks, servers, storage, applications and services) that can be rapidly provisioned and released with minimal management effort or service provider interaction.

That’s pretty inclusive of on-prem, but it took the industry a decade plus to actually get here… and they did so by going to school on and learning from the public cloud offerings.

In 2018, AWS announced Outposts and that was another wake up call to the on-prem community. Externally the on-prem vendors all pointed to the validation that hybrid cloud was real — but most didn’t have a coherent offering for hybrid at the time. While they may deny it, this was a shot across the bow by AWS that caught their attention. The idea of bringing AWS to data centers was notable. The point is that the on-prem vendors responded as they saw AWS moving past the DMZ into enemy territory.

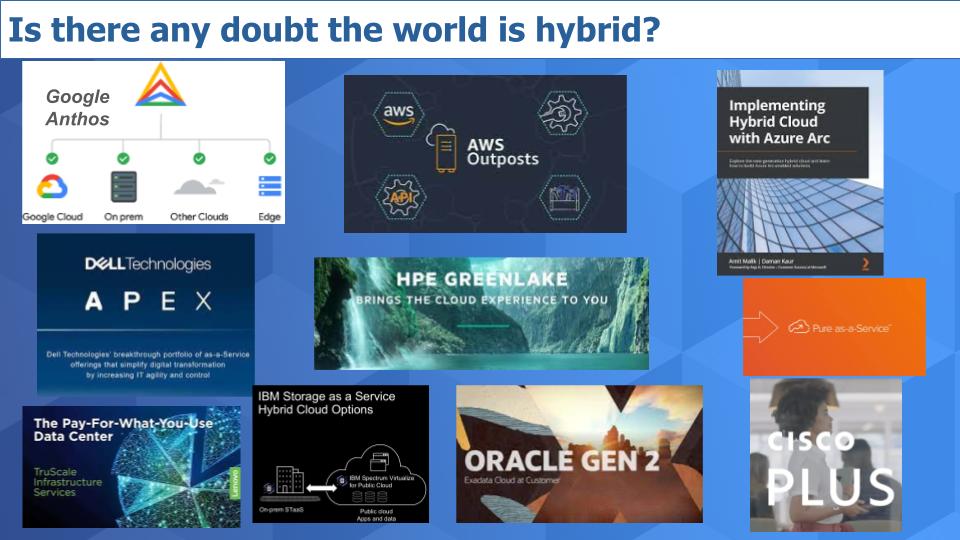

Below is a snapshot of the competitive landscape for hybrid offerings today:

All three U.S.-based hyperscalers have an offering or multiple offerings in varying forms – Outposts from Amazon, Google Anthos and Azure Arc – and all are prominent. But the real action today is from the on-prem vendors. Every major company has launched an as-a-service offering. Most of these stemmed initially from services-led, finance-led initiatives but are evolving to true as-a-service models.

Hewlett Packard Enterprise Co.’s GreenLake is widely known and Chief Executive Anthony Neri is putting the whole company behind Service. HPE claims to be the first of the on-prem players with such an offering but actually Oracle Corp. was there first with Cloud@Customer. But it only worked with Oracle’s deficient (at the time) Gen 1 cloud. Oracle has since invested heavily in cloud infrastructure and has dramatically improved the quality of its cloud.

It’s possible as well that Microsoft Corp. could make a claim to being early with Azure Stack, but early instantiations were not as cloud-friendly as Azure Arc. Dell Technologies Inc. has responded with APEX and is going hard after this opportunity, Cisco Systems Inc. has Cisco Plus and Lenovo Group Ltd. has TrueScale. IBM Corp. also has a long services, finance-led history in this space and has announced pockets of as-a-service in areas such as storage.

Pure Storage is an example of a segment player in storage that has a strong As-a-Service offering. There are others like NetApp and Nutanix, the company which popularized hyperconverged in data centers. Notably, NetApp has signed an agreement to run its stack on AWS, similar to VMware Cloud on AWS.

These are some of the more widely known offerings in the market. The point is, the landscape is getting very crowded, so let’s break this down a bit.

AWS is bringing its programmable infrastructure model – and its own hardware – to what it calls the edge. And it looks at on-prem data centers as just another edge node. So that’s how they’re de-positioning the on-prem crowd.

But the fact is that when you really look at what Outposts can do today, it’s limited in terms of services you can run on it. But AWS is moving quickly to add features, partners and capabilities, so expect a continued rapid evolution of its model.

Azure gets its hardware from partners and has relationships with everyone. Anthos as well is a software layer and Google LLC created Kubernetes as the great equalizer, a nice open-source gift to the industry.

The cloud guys have the advantage of having clouds. The pure on-prem players don’t.

The advantage for on-prem vendors is they have mature and feature rich stacks. A good example is file storage. It’s why AWS did a deal with NetApp, for example. Its stack is much richer and more mature as it relates to supporting on-premises workloads than the cloud players.

But generally they don’t have mature cloud stacks – they’re just getting started with subscription billing, application programming interface-based offerings, salesforce compensation and an overall as-a-service mentality. And they’re each coming at this from their respective points of strength.

HPE is doing a very good job of marketing and go-to-market. It probably has the cleanest model enabled by the company’s split from HP. But it has some gaps that it needed to fill and it’s doing so through acquisitions – Ezmeral is its new data play, it just bought Zerto to facilitate backup as a service, and it has expanded partnerships to fill gaps in the portfolio.

Dell is all about the portfolio, the go-to-market prowess and its supply chain advantage. It’s very serious about as-a-service and is driving hard to win the day.

Cisco comes at this from a huge portfolio and a point of strength in networking, which maybe is a bit tougher to offer as-a-service but Cisco has a large and fast-growing subscription business in collaboration, security and other areas.

Oracle has the huge advantage of an extremely rich functionality stack and it owns a cloud, which has dramatically improved in the past few years. But Oracle is narrow to the red stack. If it wanted to, we think, Oracle could dominate the database cloud if it decided to open its cloud to competitive database offerings and run them in its cloud.

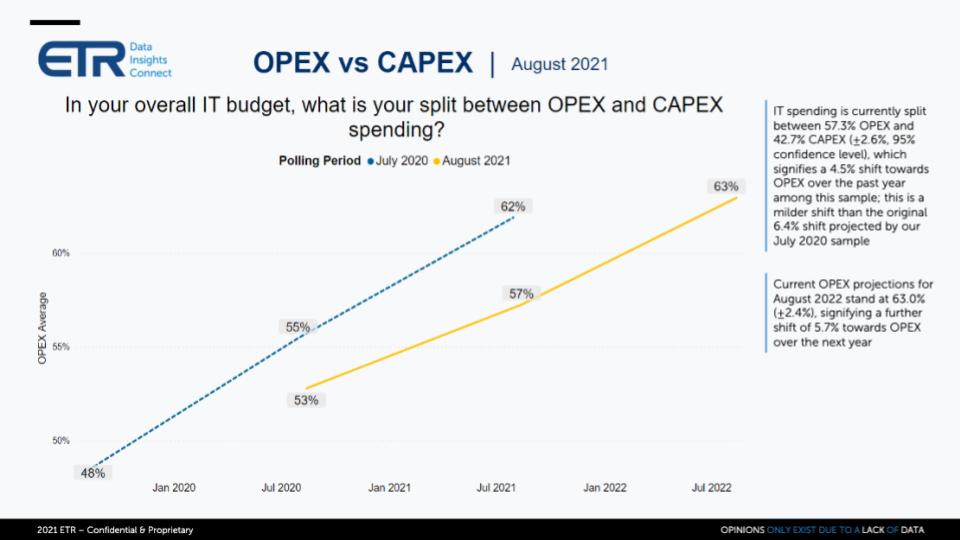

A major factor in this space for customers is the appeal of operating expenses versus capital expenses. Although there’s certainly a trend toward opex models, it’s not overwhelming and the picture is mixed. Below is some ETR data that digs a bit deeper into this topic.

This data is from an August ETR drill-down asking chief information officers and information technology buyers how their budgets split between opex and capex. The midpoint of the yellow line shows where we are today – 57% OPEX expecting to grow to 63% one year from now. That compares with the blue line, which is from the July 2020 survey, and you can see a slight acceleration toward opex that is higher than was expected last year.

There’s not a huge difference when you drill into G2000 companies, but they seem to be accelerating the shift slightly faster.

And when you dig further into industries and look at subscription versus consumption models for opex, you see about 60/40 favoring subscription models with most industries slowly moving toward consumption or usage-based models over time.

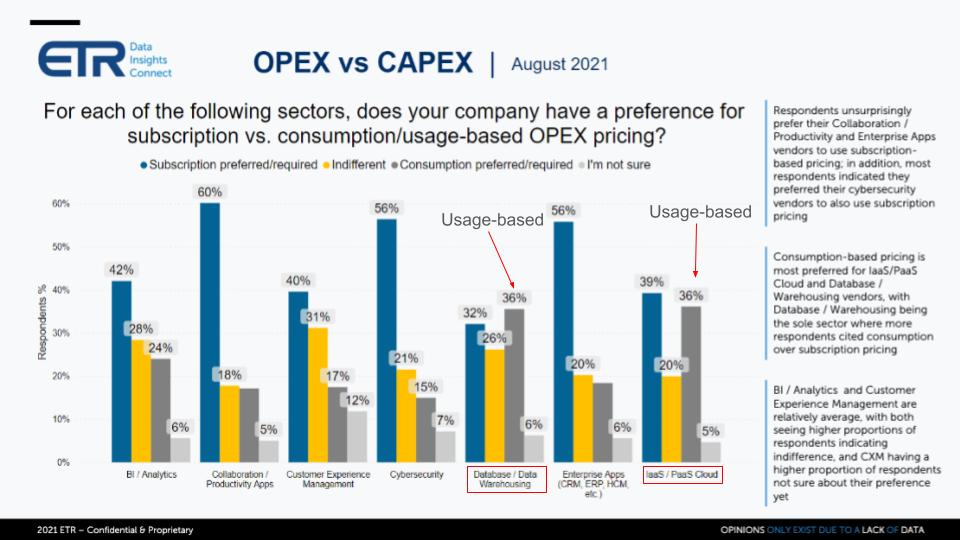

What’s perhaps more interesting is when you drill into subscription versus usage-based models by product or service area and that’s what this chart below does:

It shows by tech sector the percentage of subscription (blue bars) versus consumption or usage-based (gray bars), yellow being indifferent or don’t know. What stands out are two areas that are more usage-heavy: database/data warehousing and infrastructure as a service.

Database is likely weighted by companies such as Snowflake Inc. and offerings from AWS such as RedShift and other cloud databases from Azure and Google. But the IaaS piece, while not surprising, is relevant because most of the legacy vendor as-a-service offerings are borrowing from a SaaS-oriented subscription model with a hardware twist.

In other words, as a customer, you’re committing to a term and a minimum spend over the life of that term – to account for the hardware and headroom the vendor is installing. And you’re then paying by the drink for consumption above that minimum threshold.

So it’s a hybrid subscription/consumption model, which is compelling for customers. They can lock into a conservative threshold that they’re likely to absorb and then they can “flex up” to accommodate any surges in demand. There are nuances and hidden charges that customers need to consider but the concept is attractive.

We’ve been reporting what would really be interesting if one of the on-prem penguins on the iceberg would actually offer a true consumption model as a disruptive move to the industry and take the risk. We think that might happen once they feel comfortable with the financial model and they have nailed product market fit. But right now the model is what it is, and even AWS with Outposts requires a minimum commitment or threshold.

We’d love to see someone take a chance and offer true cloud consumption pricing. This would foster more experimentation and lower risk entry points for customers. And it would be more aligned with a true IaaS pricing model.

Let’s take a look at some of these players and see what kind of spending momentum they have in the ETR data.

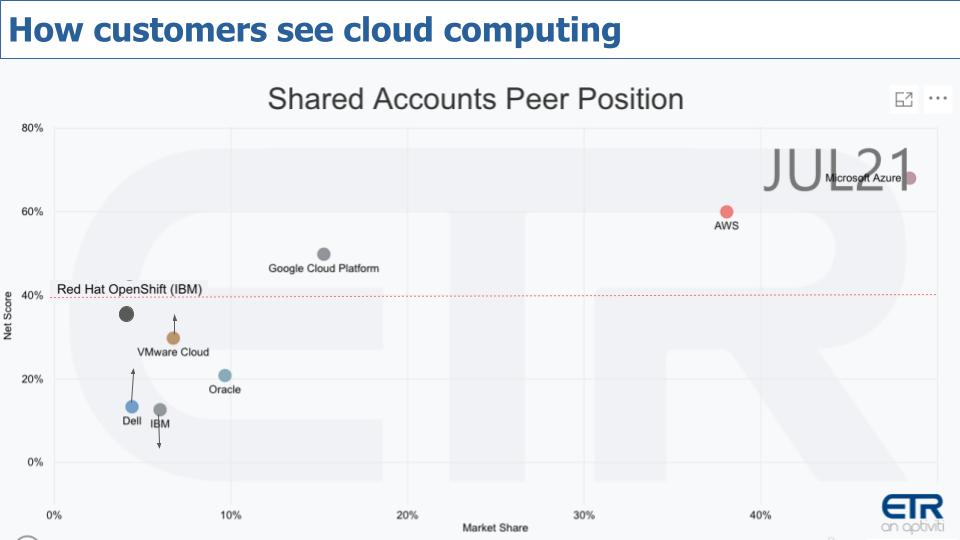

This chart above is our popular XY view. It plots Net Score or spending velocity on the Y axis and Market Share – or pervasiveness in the data set on the X axis. This is cut by cloud computing vendors as defined by the nearly 1,500 respondents in the ETR survey.

A couple of points here: Note the red line is the elevated level – anything above that is considered really robust spending momentum. Not surprisingly, Azure, AWS and Google are above the line – Azure and AWS always battle it out for top share of voice in the survey on the horizontal axis.

Note that this is the July survey, but ETR gave us a sneak peek at the early October results that they’ll be releasing this coming week. Dell Cloud and VMware Cloud (this is VCF, not VMware Cloud on AWS, which is a separate beast) are moving up on the Y axis as indicated by the arrows. IBM is moving down. And Oracle is level at a respectable 20%+ on the Y axis. Interestingly, HPE and Lenovo don’t show up in the cloud taxonomy and neither does Cisco. We believe ETR poses this as an open-ended question (that is, “Who are your cloud suppliers?”), but we’ll have to double-check that.

The point is that the on-prem vendors are getting increasingly recognized by CIOs and IT buyers as offering cloud experiences. This links back to the 2009 Chuck Hollis diagram where he laid this out in a clean graphic. Twelve years on, we’re finally seeing his vision translate into technology offerings.

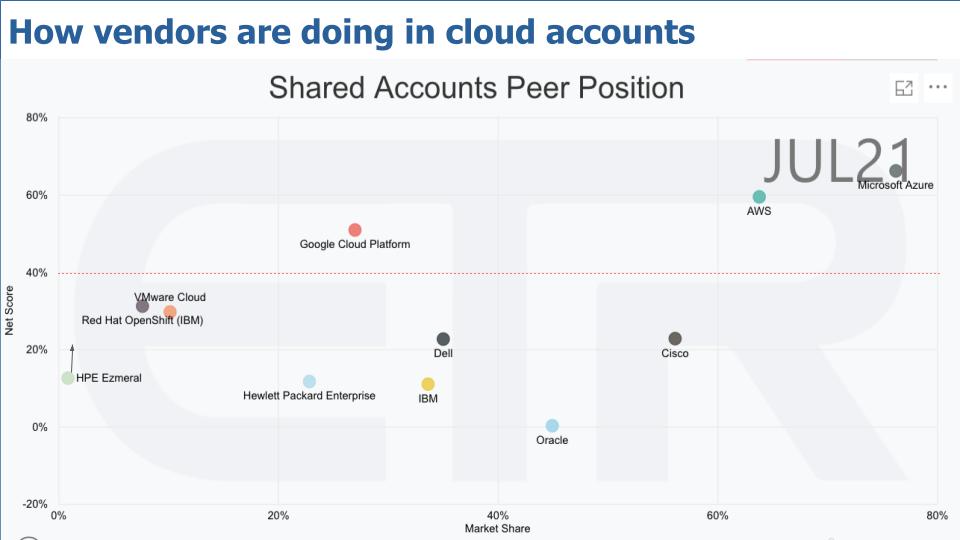

Now let’s widen the aperture a bit and cut the data by cloud accounts. In other words, how are the vendors doing inside customers that identify themselves as primarily cloud computing customers? This allows us to include some of the on-prem players that were left out of the previous chart, namely HPE and Cisco.

That’s precisely what we’ve done with the chart above. It’s a filter on 975 cloud customers and we’re able to add in Cisco and HPE. Lenovo still didn’t show up in the data. But HPE Ezmeral did and it’s moving forward in the October survey per our sneak peek. Ezmeral is HPE’s data platform that they’ve introduced to combine the assets of MapR, Blue Data and some other development work. And you can see the broader HPE and Cisco now show up on the chart.

The point is you can see the rope in the tug-of-war starting to get taut. The public cloud guys have both momentum and big account presence but the on-prem folks also have big footprints, rich stacks and many have strong services arms that will serve them well in the hybrid contest.

Let’s wrap with some comments about how this will shake out and some markers we can watch that will serve as indicators of how well the on-prem players are progressing in their march to become cloud companies.

The first thing is that we’re starting to hear the right language come out of the vendor community. The idea that they’re investing in a layer to abstract the complexity of the underlying cloud and on-prem infrastructure and turning the world into a programmable interface to resources.

If you haven’t see Greylock’s “Castles in the Cloud” project, it’s worth a look. Jerry Chen is leading the effort to understand where the ecosystem is adding value on top of the hyperscalers’ capex buildouts. It’s the ultimate white-space map. The effort is startup-centric, but we believe the companies mentioned in this post as well as others with large on-prem estates will be a major factor in this new cloud ecosystem.

One thing we want to watch: As this abstraction layer is built out, what access will be available to developers to underlying primitives and APIs in the public cloud? VMware has been clear on this: It will facilitate that deep-level access. Red Hat as well appears to be doing so. Watch to the degree it enables such capabilities. Will it connect via APIs and services to higher-level platforms such as Tanzu or OpenShift, or will it facilitate developer access to deep cloud-native services?

There is no obvious answer. Although we believe this is the right direction, it’s also hard and will require lots of resources. We would say that, at this point, each company has its respective strengths and weaknesses. We see HPE mostly today focused on making its on-prem offerings work like a cloud, whereas some of the others, VMware, Dell and Cisco, are stressing to a greater degree in our opinion enabling multicloud and edge connections. Not that HPE isn’t open to that, but its marketing is more on-prem-leaning in our view.

There’s nothing wrong with that per se and it’s more achievable in the short term. However, longer-term we believe cross cloud and edge data management will expand total markets.

One other note: Virtually all of the traditional vendors in our view are still somewhat defensive about the public cloud – although we would say much less so each day. Increasingly they look at public cloud as an opportunity to build value on top of – as is the concept behind Castles in the Cloud and some of our previous reporting.

As we said earlier, the on-prem players all have a ways to go. They’re in the early stages of figuring out what a cloud operating model looks like, what services to offer and how to pay sellers and partners. The public cloud vendors are miles ahead. At the same time, the public cloud vendors are navigating into new on-prem territory and are immature in many cases, especially as it relates to the high-touch services model.

In some respects Oracle is in the best position here in terms of hybrid maturity – but again it’s narrowly focused on the red stack. We would generally say the same for Pure Storage and NetApp — perhaps more mature in as-a-service but narrowly focused on storage.

One of the hallmarks of the public cloud is optionality of tooling. Just go to the AWS Marketplace and scan the dozens of categories, thousands of vendors, numerous pricing options (including free) and multiple delivery options. AWS has one of everything in its marketplace and you can buy directly from your AWS console. So watch how the hybrid cloud plays out in terms of partner inclusion and ease of doing business.

This is by far the most important and biggest hole in the hybrid portfolios outside the public cloud players. If you’re going to build infrastructure as code, whom do you expect to code it? How are the on-prem players cultivating developer communities?

IBM paid $34 billion on Red Hat to buy its way in to the developer community and it’s working to a degree. Actually, by today’s valuation terms that’s looking like a good buy. But still, that cash outlay is equal to one-third of IBM’s revenue. So it’s a big, big bet on OpenShift. But IBM’s infrastructure strategy is fragmented, as is its software-as-a-service portfolio. The IBM public cloud as measured in the ETR spending data is not encouraging. Analyst ratings of IBM’s cloud consistently put it behind the leaders. So it has a lot of work to do. But it has a developer play that is stronger than any of the other on-prem players thanks to Red Hat.

Now VMware, by cobbling together the misfit developer toys of the remnants from the EMC federation, including Pivotal, is trying to get there.

Cisco has DevNet but that’s basicallyCisco Certified Internetwork Experts or CCIEs learning to code in languages such as Python and not necessarily true developers. But it’s a start and it’s investing in a community, leveraging its champions. Dell can do the same with, for example, EMC storage administrators.

Oracle bought Sun Microsystems Inc. to get Java and that’s a large community of developers, but even so, when you compare AWS and Microsoft ecosystems to these others, it’s not even close.

Pure’s acquisition of Portworx, again, while narrowly focused, is a good move and instructive of the market changes and the shift to programmable infrastructure.

How does this relate to the edge? Well, we’re not going to talk much about the “internet of things” today, but suffice it to say, developers will win the edge and right now, they’re coding in the cloud. Of course, they’re often coding in the cloud and moving work on-prem with containers, but watch how sticky that model is for the respective players. We believe those with the strongest developer ecosystems will be in a much better position to thrive in the edge thanks to its diversity and fragmentation.

Another hallmark of cloud is rapid expansion of features. The public cloud players don’t appear to be slowing down and the on-prem folks seem to be accelerating, but watch how quickly the newbies of as-a-service can add functionality.

HPE appears to be on a rapid cadence. Dell is as well. Cisco has so much going on that we’ll likely see it accelerate cloud features and others will have to follow suit.

The question is, can they keep up with the hyperscale cloud players? Will the move to on-prem for the hyperscalers slow down their innovation cadence? There’s no evidence of that today, and by all accounts the cloud players are much further up the learning curve with regard to launching new services and accommodating ecosystem innovations.

Watch how as-a-service affects the income statements and how the companies deal with that. As you shift to deferred revenue models, it will hurt profitability – and we’re not worried about that as long as the companies communicate to Wall Street and they’re transparent, meaning they don’t shift reporting definitions every two years.

But watch for metrics around retention/churn, revenue performance obligations, billings versus bookings, increased average contract values, cohort selling, lifetime value, acquisition costs and the impact on both gross margin and operating margin. These will be key indicators of success and the proof in the pudding of the transition to cloud. It should be positive for these companies assuming they get the product market fit right and can create a flywheel with their respective ecosystems and partner channels — and achieve low churn rates.

We’re sure you can think of other important factors – do let us know – but these are the ones that came to mind, so we’ll leave it there for today.

Remember we publish each week on Wikibon and SiliconANGLE. These episodes are all available as podcasts wherever you listen.

Email david.vellante@siliconangle.com, DM @dvellante on Twitter and comment on our LinkedIn posts.

Also, check out this ETR Tutorial we created, which explains the spending methodology in more detail. Note: ETR is a separate company from Wikibon and SiliconANGLE. If you would like to cite or republish any of the company’s data, or inquire about its services, please contact ETR at legal@etr.ai.

Here’s the full video analysis:

All statements made regarding companies or securities are strictly beliefs, points of view and opinions held by SiliconANGLE media, Enterprise Technology Research, other guests on theCUBE and guest writers. Such statements are not recommendations by these individuals to buy, sell or hold any security. The content presented does not constitute investment advice and should not be used as the basis for any investment decision. You and only you are responsible for your investment decisions.

THANK YOU